When he learned in 1995 that he had Alzheimer’s disease, William Utermohlen, an American artist living in London, immediately began work on an ambitious series of self-portraits. The artist pursued this project over an eight-year period, adapting his style to the growing limitations of his perception and motor skills and creating images that powerfully documented his experience of his illness. The resulting body of work serves as a unique artistic, medical, and personal record of one man’s struggle with dementia.

Category Archives: Questions

Is there originality in any work of art?

While contemporary performance may borrow

either aesthetic strategies

or apparent ideological gestures from the past,

this borrowing

makes no claims to invest the material

or the aesthetic strategy

with a historical “thought.”

The process in which a block of material

or a analogous strategy

incorporates a prior unit or technique

in a form of quotation

that makes no reference to what is prior

other than its status as

something borrowed, appropriated, taken up

in the moment of performance.

Is there originality in any work of art?

Have I thought myself

into the corner of defining art itself

as a manipulation of existing languages,

tropes, gestures

that may vary in craft

but always re-presents or reproduces

what is prior.

Productions of Shakespeare, Ibsen, O’Neill

are only simulations,

in no way a production of originality;

while contemporary performance

frees itself from that pretense.

Of course

this is bull shit

as that freedom from pretense

is itself a claim for authenticity.

Virginia Woolf: “Middlebrow”

To The Editor of the “New Statesman”

Sir,

Will you allow me to draw your attention to the fact that in a review of a book by me (October ) your reviewer omitted to use the word Highbrow? The review, save for that omission, gave me so much pleasure that I am driven to ask you, at the risk of appearing unduly egotistical, whether your reviewer, a man of obvious intelligence, intended to deny my claim to that title? I say “claim,” for surely I may claim that title when a great critic, who is also a great novelist, a rare and enviable combination, always calls me a highbrow when he condescends to notice my work in a great newspaper; and, further, always finds space to inform not only myself, who know it already, but the whole British Empire, who hang on his words, that I live in Bloomsbury? Is your critic unaware of that fact too? Or does he, for all his intelligence, maintain that it is unnecessary in reviewing a book to add the postal address of the writer?

His answer to these questions, though of real value to me, is of no possible interest to the public at large. Of that I am well aware. But since larger issues are involved, since the Battle of the Brows troubles, I am told, the evening air, since the finest minds of our age have lately been engaged in debating, not without that passion which befits a noble cause, what a highbrow is and what a lowbrow, which is better and which is worse, may I take this opportunity to express my opinion and at the same time draw attention to certain aspects of the question which seem to me to have been unfortunately overlooked?

Now there can be no two opinions as to what a highbrow is. He is the man or woman of thoroughbred intelligence who rides his mind at a gallop across country in pursuit of an idea. That is why I have always been so proud to be called highbrow. That is why, if I could be more of a highbrow I would. I honour and respect highbrows. Some of my relations have been highbrows; and some, but by no means all, of my friends. To be a highbrow, a complete and representative highbrow, a highbrow like Shakespeare, Dickens, Byron, Shelley, Keats, Charlotte Bronte, Scott, Jane Austen, Flaubert, Hardy or Henry James — to name a few highbrows from the same profession chosen at random — is of course beyond the wildest dreams of my imagination. And, though I would cheerfully lay myself down in the dust and kiss the print of their feet, no person of sense will deny that this passionate preoccupation of theirs — riding across country in pursuit of ideas — often leads to disaster. Undoubtedly, they come fearful croppers. Take Shelley — what a mess he made of his life! And Byron, getting into bed with first one woman and then with another and dying in the mud at Missolonghi. Look at Keats, loving poetry and Fanny Brawne so intemperately that he pined and died of consumption at the age of twenty-six. Charlotte Bronte again — I have beep assured on good authority that Charlotte Bronte was, with the possible exception of Emily, the worst governess in the British Isles. Then there was Scott — he went bankrupt, and left, together with a few magnificent novels, one house, Abbotsford, which is perhaps the ugliest in the whole Empire. But surely these instances are enough — I need not further labour the point that highbrows, for some reason or another, are wholly incapable of dealing successfully with what is called real life. That is why, and here I come to a point that is often surprisingly ignored, they honour so wholeheartedly and depend so completely upon those who are called lowbrows. By a lowbrow is meant of course a man or a woman of thoroughbred vitality who rides his body in pursuit of a living at a gallop across life. That is why I honour and respect lowbrows — and I have never known a highbrow who did not. In so far as I am a highbrow (and my imperfections in that line are well known to me) I love lowbrows; I study them; I always sit next the conductor in an omnibus and try to get him to tell me what it is like — being a conductor. In whatever company I am I always try to know what it is like — being a conductor, being a woman with ten children and thirty-five shillings a week, being a stockbroker, being an admiral, being a bank clerk, being a dressmaker, being a duchess, being a miner, being a cook, being a prostitute. All that lowbrows do is of surpassing interest and wonder to me, because, in so far as I am a highbrow, I cannot do things myself.

This brings me to another point which is also surprisingly overlooked. Lowbrows need highbrows and honour them just as much as highbrows need lowbrows and honour them. This too is not a matter that requires much demonstration. You have only to stroll along the Strand on a wet winter’s night and watch the crowds lining up to get into the movies. These lowbrows are waiting, after the day’s work, in the rain, sometimes for hours, to get into the cheap seats and sit in hot theatres in order to see what their lives look like. Since they are lowbrows, engaged magnificently and adventurously in riding full tilt from one end of life to the other in pursuit of a living, they cannot see themselves doing it. Yet nothing interests them more. Nothing matters to them more. It is one of the prime necessities of life to them — to be shown what life looks like. And the highbrows, of course, are the only people who can show them. Since they are the only people who do not do things, they are the only people who can see things being done. This is so — and so it is I am certain; nevertheless we are told — the air buzzes with it by night, the press booms with it by day, the very donkeys in the fields do nothing but bray it, the very curs in the streets do nothing but bark it —“Highbrows hate lowbrows! Lowbrows hate highbrows!”— when highbrows need lowbrows, when lowbrows need highbrows, when they cannot exist apart, when one is the complement and other side of the other! How has such a lie come into existence? Who has set this malicious gossip afloat?

There can be no doubt about that either. It is the doing of the middlebrows. They are the people, I confess, that I seldom regard with entire cordiality. They are the go-betweens; they are the busy-bodies who run from one to the other with their tittle tattle and make all the mischief — the middlebrows, I repeat. But what, you may ask, is a middlebrow? And that, to tell the truth, is no easy question to answer. They are neither one thing nor the other. They are not highbrows, whose brows are high; nor lowbrows, whose brows are low. Their brows are betwixt and between. They do not live in Bloomsbury which is on high ground; nor in Chelsea, which is on low ground. Since they must live somewhere presumably, they live perhaps in South Kensington, which is betwixt and between. The middlebrow is the man, or woman, of middlebred intelligence who ambles and saunters now on this side of the hedge, now on that, in pursuit of no single object, neither art itself nor life itself, but both mixed indistinguishably, and rather nastily, with money, fame, power, or prestige. The middlebrow curries favour with both sides equally. He goes to the lowbrows and tells them that while he is not quite one of them, he is almost their friend. Next moment he rings up the highbrows and asks them with equal geniality whether he may not come to tea. Now there are highbrows — I myself have known duchesses who were highbrows, also charwomen, and they have both told me with that vigour of language which so often unites the aristocracy with the working classes, that they would rather sit in the coal cellar, together, than in the drawing-room with middlebrows and pour out tea. I have myself been asked — but may I, for the sake of brevity, cast this scene which is only partly fictitious, into the form of fiction? — I myself, then, have been asked to come and “see” them — how strange a passion theirs is for being “seen”! They ring me up, therefore, at about eleven in the morning, and ask me to come to tea. I go to my wardrobe and consider, rather lugubriously, what is the right thing to wear? We highbrows may be smart, or we may be shabby; but we never have the right thing to wear. I proceed to ask next: What is the right thing to say? Which is the right knife to use? What is the right book to praise? All these are things I do not know for myself. We highbrows read what we like and do what we like and praise what we like. We also know what we dislike — for example, thin bread and butter tea. The difficulty of eating thin bread and butter in white kid gloves has always seemed to me one of life’s more insuperable problems. Then I dislike bound volumes of the classics behind plate glass. Then I distrust people who call both Shakespeare and Wordsworth equally “Bill”— it is a habit moreover that leads to confusion. And in the matter of clothes, I like people either to dress very well; or to dress very badly; I dislike the correct thing in clothes. Then there is the question of games. Being a highbrow I do not play them. But I love watching people play who have a passion for games. These middlebrows pat balls about; they poke their bats and muff their catches at cricket. And when poor Middlebrow mounts on horseback and that animal breaks into a canter, to me there is no sadder sight in all Rotten Row. To put it in a nutshell (in order to get on with the story) that tea party was not wholly a success, nor altogether a failure; for Middlebrow, who writes, following me to the door, clapped me briskly on the back, and said “I’m sending you my book!” (Or did he call it “stuff?”) And his book comes — sure enough, though called, so symbolically, Keepaway, [Keepaway is the name of a preparation used to distract the male dog from the female at certain seasons] it comes. And I read a page here, and I read a page there (I am breakfasting, as usual, in bed). And it is not well written; nor is it badly written. It is not proper, nor is it improper — in short it is betwixt and between. Now if there is any sort of book for which I have, perhaps, an imperfect sympathy, it is the betwixt and between. And so, though I suffer from the gout of a morning — but if one’s ancestors for two or three centuries have tumbled into bed dead drunk one has deserved a touch of that malady — I rise. I dress. I proceed weakly to the window. I take that book in my swollen right hand and toss it gently over the hedge into the field. The hungry sheep — did I remember to say that this part of the story takes place in the country? — the hungry sheep look up but are not fed.

But to have done with fiction and its tendency to lapse into poetry — I will now report a perfectly prosaic conversation in words of one syllable. I often ask my friends the lowbrows, over our muffins and honey, why it is that while we, the highbrows, never buy a middlebrow book, or go to a middlebrow lecture, or read, unless we are paid for doing so, a middlebrow review, they, on the contrary, take these middlebrow activities so seriously? Why, I ask (not of course on the wireless), are you so damnably modest? Do you think that a description of your lives, as they are, is too sordid and too mean to be beautiful? Is that why you prefer the middlebrow version of what they have the impudence to call real humanity? — this mixture of geniality and sentiment stuck together with a sticky slime of calves-foot jelly? The truth, if you would only believe it, is much more beautiful than any lie. Then again, I continue, how can you let the middlebrows teach you how to write? — you, who write so beautifully when you write naturally, that I would give both my hands to write as you do — for which reason I never attempt it, but do my best to learn the art of writing as a highbrow should. And again, I press on, brandishing a muffin on the point of a tea spoon, how dare the middlebrows teach you how to read — Shakespeare for instance? All you have to do is to read him. The Cambridge edition is both good and cheap. If you find Hamlet difficult, ask him to tea. He is a highbrow. Ask Ophelia to meet him. She is a lowbrow. Talk to them, as you talk to me, and you will know more about Shakespeare than all the middlebrows in the world can teach you — I do not think, by the way, from certain phrases that Shakespeare liked middlebrows, or Pope either.

To all this the lowbrows reply — but I cannot imitate their style of talking — that they consider themselves to be common people without education. It is very kind of the middlebrows to try to teach them culture. And after all, the lowbrows continue, middlebrows, like other people, have to make money. There must be money in teaching and in writing books about Shakespeare. We all have to earn our livings nowadays, my friends the lowbrows remind me. I quite agree. Even those of us whose Aunts came a cropper riding in India and left them an annual income of four hundred and rfifty pounds, now reduced, thanks to the war and other luxuries, to little more than two hundred odd, even we have to do that. And we do it, too, by writing about anybody who seems amusing — enough has been written about Shakespeare — Shakespeare hardly pays. We highbrows, I agree, have to earn our livings; but when we have earned enough to live on, then we live. When the middlebrows, on the contrary, have earned enough to live on, they go on earning enough to buy — what are the things that middlebrows always buy? Queen Anne furniture (faked, but none the less expensive); first editions of dead writers, always the worst; pictures, or reproductions from pictures, by dead painters; houses in what is called “the Georgian style”— but never anything new, never a picture by a living painter, or a chair by a living carpenter, or books by living writers, for to buy living art requires living taste. And, as that kind of art and that kind of taste are what middlebrows call “highbrow,” “Bloomsbury,” poor middlebrow spends vast sums on sham antiques, and has to keep at it scribbling away, year in, year out, while we highbrows ring each other up, and are off for a day’s jaunt into the country. That is the worst of course of living in a set — one likes being with one’s friends.

Have I then made my point clear, sir, that the true battle in my opinion lies not between highbrow and lowbrow, but between highbrows and lowbrows joined together in blood brotherhood against the bloodless and pernicious pest who comes between? If the B.B.C. stood for anything but the Betwixt and Between Company they would use their control of the air not to stir strife between brothers, but to broadcast the fact that highbrows and lowbrows must band together to exterminate a pest which is the bane of all thinking and living. It may be, to quote from your advertisement columns, that “terrifically sensitive” lady novelists overestimate the dampness and dinginess of this fungoid growth. But all I can say is that when, lapsing into that stream which people call, so oddly, consciousness, and gathering wool from the sheep that have been mentioned above, I ramble round my garden in the suburbs, middlebrow seems to me to be everywhere. “What’s that?” I cry. “Middlebrow on the cabbages? Middlebrow infecting that poor old sheep? And what about the moon?” I look up and, behold, the moon is under eclipse. “Middlebrow at it again!” I exclaim. “Middlebrow obscuring, dulling, tarnishing and coarsening even the silver edge of Heaven’s own scythe.” (I “draw near to poetry,” see advt.) And then my thoughts, as Freud assures us thoughts will do, rush (Middlebrow’s saunter and simper, out of respect for the Censor) to sex, and I ask of the sea-gulls who are crying on desolate sea sands and of the farm hands who are coming home rather drunk to their wives, what will become of us, men and women, if Middlwbrow has his way with us, and there is only a middle sex but no husbands or wives? The next remark I address with the utmost humility to the Prime Minister. “What, sir,” I demand, “will be the fate of the British Empire and of our Dominions Across the Seas if Middlebrows prevail? Will you not, sir, read a pronouncement of an authoritative nature from Broadcasting House?”

Such are the thoughts, such are the fancies that visit “cultured invalidish ladies with private means” (see advt.) when they stroll in their suburban gardens and look at the cabbages and at the red brick villas that have been built by middlebrows so that middlebrows may look at the view. Such are the thoughts “at once gay and tragic and deeply feminine” (see advt.) of one who has not yet “been driven out of Bloomsbury” (advt. again), a place where lowbrows and highbrows live happily together on equal terms and priests are not, nor priestesses, and, to be quite frank, the adjective “priestly” is neither often heard nor held in high esteem. Such are the thoughts of one who will stay in Bloomsbury until the Duke of Bedford, rightly concerned for the respectability of his squares, raises the rent so high that Bloomsbury is safe for middlebrows to live in. Then she will leave.

May I conclude, as I began, by thanking your reviewer for his very courteous and interesting review, but may I tell him that though he did not, for reasons best known to himself, call me a highbrow, there is no name in the world that I prefer? I ask nothing better than that all reviewers, for ever, and everywhere, should call me a highbrow. I will do my best to oblige them. If they like to add Bloomsbury, W.C.1, that is the correct postal address, and my telephone number is in the Directory. But if your reviewer, or any other reviewer, dares hint that I live in South Kensington, I will sue him for libel. If any human being, man, woman, dog, cat or half-crushed worm dares call me “middlebrow” I will take my pen and stab him, dead. Yours etc.,

Virginia Woolf.

Keats: Bright Star

Keats copied Bright Star into his volume of “The Poetical Works of William Shakespeare”, opposite Shakespeare’s poem, A Lover’s Complaint as he sailed to Rome.

Bright star, would I were steadfast as thou art —

Not in lone splendour hung aloft the night

And watching, with eternal lids apart,

Like Nature’s patient, sleepless Eremite,

The moving waters at their priestlike task

Of pure ablution round earth’s human shores,

Or gazing on the new soft-fallen mask

Of snow upon the mountains and the moors —

No — yet still stedfast, still unchangeable,

Pillow’d upon my fair love’s ripening breast,

To feel for ever its soft swell and fall,

Awake for ever in a sweet unrest,

Still, still to hear her tender-taken breath,

And so live ever — or else swoon to death.

Best condolence ever…

Stewart Stern, passed away this month.

a screenwriter most noted for Rebel Without a Cause

was nominated for an Oscar on two occasions,

won an Emmy for the teleplay of Sybil

worked on Dennis Hopper’s The Last Movie

and to James Dean’s aunt and uncle

he wrote one of the most moving and beautiful

condolence letters ever…

Hollywood 46, California

[Redacted]

12 October, 1955

Dear Marcus and Mrs. Winslow:

I shall never forget that silent town on that particular sunny day. And I shall never forget the care with which people set their feet down — so carefully on the pavements — as if the sound of a suddenly scraped heel might disturb the sleep of a boy who slept soundly. And the whispering. Do you remember one voice raised beyond a whisper in all those reverential hours of goodbye? I don’t. A whole town struck silent, a whole town with love filling its throat, a whole town wondering why there had been so little time in which to give the love away.

Gandhi once said that if all those doomed people at Hiroshima had lifted their faces to the plane that hovered over them and if they had sent up a single sigh of spiritual protest, the pilot would not have dropped his bomb. That may or may not be. But I am sure, I am certain, I know — that the great wave of warmth and affection that swept upward from Fairmount has wrapped itself around that irresistible phantom securely and forever.

Nor shall I forget the land he grew on or the stream he fished, or the straight, strong, gentle people whom he loved to talk about into the nights when he was away from them. His great-grandma whose eyes have seen half of America’s history, his grandparents, his father, his treasured three of you — four generations for the coiling of a spring — nine decades of living evidence of seed and turning earth and opening kernel. It was a solid background and one to be envied. The spring, released, flung him into our lives and out again. He burned an unforgettable mark in the history of his art and changed it as surely as Duse, in her time, changed it.

A star goes wild in the places beyond air — a dark star born of coldness and invisible. It hits the upper edges of our atmosphere and look! It is seen! It flames and arcs and dazzles. It goes out in ash and memory. But its after-image remains in our eyes to be looked at again and again. For it was rare. And it was beautiful. And we thank God and nature for sending it in front of our eyes.

So few things blaze. So little is beautiful. Our world doesn’t seem equipped to contain its brilliance too long. Ecstasy is only recognizable when one has experienced pain. Beauty only exists when set against ugliness. Peace is not appreciated without war ahead of it. How we wish that life could support only the good. But it vanishes when its opposite no longer exists as a setting. It is a white marble on unmelting snow. And Jimmy stands clear and unique in a world where much is synthetic and dishonest and drab. He came and rearranged our molecules.

I have nothing of Jim’s — nothing to touch or look at except the dried mud that clung to my shoes — mud from the farm that grew him — and a single kernel of seed corn from your barn. I have nothing more than this and I want nothing more. There is no need to touch something he touched when I can still feel his hand on me. He gave me his faith, unquestioningly and trustfully — once when he said he would play in REBEL because he knew I wanted him to, and once when he tried to get LIFE to let me write his biography. He told me he felt I understood him and if LIFE refused to let me do the text for the pictures Dennis took, he would refuse to let the magazine do a spread on him at all. I managed to talk him out of that, knowing that LIFE had to use its own staff writers, but will never forget how I felt when he entrusted his life to me. And he gave me, finally, the gift of his art. He spoke my words and played my scenes better than any other actor of our time or of our memory could have done. I feel that there are other gifts to come from him — gifts for all of us. His influence did not stop with his breathing. It walks with us and will profoundly affect the way we look at things. From Jimmy I have already learned the value of a minute. He loved his minutes and I shall now love mine.

These words aren’t clear. But they are clearer than what I could have said to you last week.

I write from the depths of my appreciation — to Jimmy for having touched my life and opened my eyes — to you for having grown him all those young years and for having given him your love — to you for being big enough and humane enough to let me come into your grief as a stranger and go away a friend.

When I drove away the sky at the horizon was yellowing with twilight and the trees stood clean against it. The banks of flowers covering the grave were muted and grayed by the coming of evening and had yielded up their color to the sunset. I thought — here’s where he belongs — with this big darkening sky and this air that is thirst-quenching as mountain water and this century of family around him and the cornfield crowding the meadow where his presence will be marked. But he’s not in the meadow. He’s out there in the corn. He’s hunting the winter’s rabbit and the summer’s catfish. He has a hand on little Mark’s shoulder and a sudden kiss for you. And he has my laughter echoing his own at the great big jokes he saw and showed to me — and he’s here, living and vivid and unforgettable forever, far too mischievous to lie down long.

My love and gratitude, to you and young Mark,

Stewart

The function of the hero, John Berger

“The function of the hero in art is to inspire the reader or spectator to continue in the same spirit from where he, the hero, leaves off. He must release the spectator’s potentiality, for potentiality is the historic force behind nobility. And to do this the hero must be typical of the characters and class who at that time only need to be made aware of their heroic potentiality in order to be able to make their society juster and nobler. Bourgeois culture is no longer capable of producing heroes. On the highbrow level it only produces characters who are embodied consolations for defeat, and on the lowbrow level it produces idols—stars, TV “personalities,” pin-ups. The function of the idol is the exact opposite to that of the hero. The idol is self-sufficient; the hero never is. The idol is so superficially desirable, spectacular, witty, happy that he or she merely supplies a context for fantasy and therefore, instead of inspiring, lulls. The idol is based on the appearance of perfection; but never on the striving towards it.”

John Berger (b. 1926), British author, painter. “A Few Useful Definitions,” Permanent Red, Writers and Readers Publ. (1960).

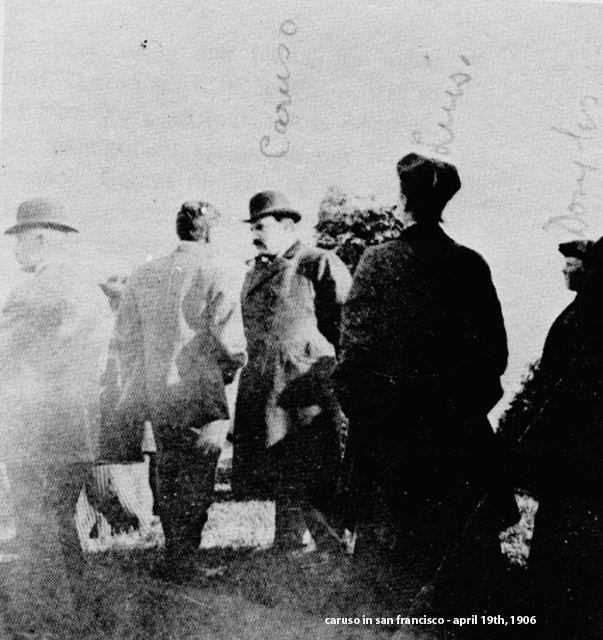

Enrico Caruso’s 1906 Eyewitness Account of 1906 San Francisco Earthquake

You ask me to say what I saw and what I did during the terrible days which witnessed the destruction of San Francisco? Well, there have been many accounts of my so-called adventures published in the American papers, and most of them have not been quite correct. Some of the papers said that I was terribly frightened, that I went half crazy with fear, that I dragged my valise out of the hotel into the square and sat upon it and wept; but all this is untrue. I was frightened, as many others were, but I did not lose my head. I was stopping at the [Palace] Hotel, where many of my fellow-artists were staying, and very comfortable it was. I had a room on the fifth floor, and on Tuesday evening, the night before the great catastrophe, I went to bed feeling very contented. I had sung in “Carmen” that night, and the opera had one with fine eclat. We were all pleased, and, as I said before, I went to bed that night feeling happy and contented.

But what an awakening! You must know that I am not a very heavy sleeper—I always wake early, and when I feel restless I get up and go for a walk. So on the Wednesday morning early I wake up about 5 o’clock, feeling my bed rocking as though I am in a ship on the ocean, and for a moment I think I am dreaming that I am crossing the water on my way to my beautiful country. And so I take no notice for the moment, and then, as the rocking continues, I get up and go to the window, raise the shade and look out. And what I see makes me tremble with fear. I see the buildings toppling over, big pieces of masonry falling, and from the street below I hear the cries and screams of men and women and children.

I remain speechless, thinking I am in some dreadful nightmare, and for something like forty seconds I stand there, while the buildings fall and my room still rocks like a boat on the sea. And during that forty seconds I think of forty thousand different things. All that I have ever done in my life passes before me, and I remember trivial things and important things. I think of my first appearance in grand opera, and I feel nervous as to my reception, and again I think I am going through last night’s “Carmen.”

And then I gather my faculties together and call for my valet. He comes rushing in quite cool, and, without any tremor in his voice, says: “It is nothing.” But all the same he advises me to dress quickly and go into the open, lest the hotel fall and crush us to powder. By this time the plaster on the ceiling has fallen in a great shower, covering the bed and the carpet and the furniture, and I, to, begin to think it is time to “get busy.” My valet gives me some clothes; I know not what the garments are but I get into a pair of trousers and into a coat and draw some socks on and my shoes, and every now and again the room trembles, so that I jump and feel very nervous. I do not deny that I feel nervous, for I still think the building will fall to the ground and crush us. And all the time we hear the sound of crashing masonry and the cries of frightened people.

Then we run down the stairs and into the street, and my valet, brave fellow that he is, goes back and bundles all my things into trunks and drags them down six flights of stairs and out into the open one by one. While he is gone for another and another, I watch those that have already arrived, and presently someone comes and tries to take my trunks saying they are his. I say, “no, they are mine”; but he does not go away. Then a soldier comes up to me; I tell him that this man wants to take my trunks, and that I am Caruso, the artist who sang in “Carmen” the night before. He remembers me and makes the man who takes an interest in my baggage “skiddoo” as Americans say.

Then I make my way to Union Square, where I see some of my friends, and one of them tells me he has lost everything except his voice, but he is thankful that he has still got that. And they tell me to come to a house that is still standing; but I say houses are not safe, nothing is safe but the open square, and I prefer to remain in a place where there is no fear of being buried by falling buildings. So I lie down in the square for a little rest, while my valet goes and looks after the luggage, and soon I begin to see the flames and all the city seems to be on fire. All the day I wander about, and I tell my valet we must try and get away, but the soldiers will not let us pass. We can find no vehicle to find our luggage, and this night we are forced to sleep on the hard ground in the open. My limbs ache yet from so rough a bed.

Then my valet succeeds in getting a man with a cart, who says he will take us to the Oakland Ferry for a certain sum, and we agree to his terms. We pile the luggage into the cart and climb in after it, and the man whips up his horse and we start.

We pass terrible scenes on the way: buildings in ruins, and everywhere there seems to be smoke and dust. The driver seems in no hurry, which makes me impatient at times, for I am longing to return to New York, where I know I shall find a ship to take me to my beautiful Italy and my wife and my little boys.

When we arrive at Oakland we find a train there which is just about to start, and the officials are very polite, take charge of my luggage, and tell me go get on board, which I am very glad to do. The trip to New York seems very long and tedious, and I sleep very little, for I can still feel the terrible rocking which made me sick. Even now I can only sleep an hour at a time, for the experience was a terrible one.

Shakespeare’s One Star reviews on Amazon

Boring boring boring boring boring boring boring boring boring boring boringness boring boring boring boring boringness boring boring boringness boring boobs ass tits balls

I would give this book one star for trying. I didn’t really enjoy it, but maybe that’s just because I don’t like love stories.

I would reccomend this to theatre people.

I tried to read Shakepeare as a kid, and couldn’t stand it. It still sucks 50 years later.

it would have been nice to hav some scene setting or descriptions

This book is very boring and doesn’t say much for the man who wrote it! Ofcourse Willy is acclaimed as the best writer of all time, but this is only because of British Media hyping the man, after 400 years.

It was ok compared to some other books I have read in the pasts but not that good

Heres what i would say to Shakespear… Welcome to America Now speak english

shakespeare was obviously taking some shortcuts here. still, a pretty good play,

I wish that William Shakespeare would have wrote it like a regular book

All and all this play is atrocious. Though it is acclaimed as the greatest work of drama ever, it is hardly that. People who say such things, have absolutely no credibility. Hamlet’s only purpose is to confuse the reader. Any intelligent person can see through his character and realize that he is little more than a feeble mind with a large vocabulary

Wasn’t such a big fan. I prefer more modern novels, without the big words

Having researched great authors as part my PhD at Princeton, it is surprising how poorly Shakespeare has written this particular book. The plot is weak and lacks imagination, the character development is all over the shop and writing style is quite muddled in places.

I hate all the stupid fairy stuff almost as much as I hate those be damn communists

The poetry could be much better.

The book has some high points and a lot of low points. Shakespeare’s wordplay is on full display but the bard has definitely been beaten by later books with the same plot but more interesting treatment. I recommend this on an uncertain day when you want a light and refreshing read of old school drama.

I’m an Arts and Letters major and you won’t find me reading Shakespeare. I don’t share the common fondness that folks nationwide has with this particular author. I think most people simply quote and adore him because he obviously heralded something new to the world of theater and literature.

I was very disappointed

Macbeth I found to be tacky with very few memorable quotes.

I’m not saying I didn’t like it – I did and it has it’s peaks and valleys, but when the good writing is so good and the bad so bad, the whole piece loses it’s magic a bit.

Would like to watch a play it sounds fun

I absolutely hated it. Don’t really know what all the hype was about. It felt like forever trying to get through it. The end could not come fast enough!

A good piece of writing, not too much to brag about though

This has to be one of the worst plays ever written, Shakespeare or no Shakespeare. While the Bard was the master of English drama, he really slipped up here. The plot makes no sense, the characters motivations are contrived, and the jokes fall flat. I have read this play hundreds of times, seen umpteen productions and films, and am astonished at the plaudits universally accorded to it.

Too much time is taken betwwen the action scenes

The utter stupidity of the script and the horrible ending drag it down.

i liked it that hal killed hotspur because in the movie hotspur was ugly and disgusting. everytime i looked at him i felt like i wanted to puke.

This book is the worst book i have ever read in my life. It was only good for making me fall asleep

This book was absolutely ridiculous. No copyright or publishing information.

The language is very poetic and the story interesting. However, the main characters are extremely shallow

This may be one of the great works of humanity, but it just doesn’t cut it for me. The gender sterotypes are nauseating, to say the least

In my opinion all of Shakespeare’s writings are long winded, drawn out words with no possibility of ever coming close to being remotly interesting. Hamlet was actually one of the most terribly boring, predictable, useless book ever written. The plot had no vital juices. The charachters were devoid of all emotion and energy. Even more devastating to the book is how it all ended. I actually got to say once Hamlet,Gertrude, and Claudius died I was leaping with joy, it was impossible to contain my excitment. Why? Because it meant that if every one is dead, well, IT IS FINALLY OVER!

There’s nothing here that tells us anything about the human condition other than what we already know and acknowledge as some of our worst traits: that we can be impulsive, gullible, stubborn, hateful, and murderous.

This was by far the worst science fiction novel I have ever watched

I think that Shakespeare made up some of the words. Also, the story was so hard to understand because Shakespeare uses so many metaphors, and doesn’t describe what is going on too well. Even if this story were written in today’s language, it still wouldn’t have appealed to me because I don’t think the plot is any good.

I’m sorry, but this book was awful. You can burn me for a heretic, but it was

i just read this book. everybody like always talks about how great it is and everything. but i don’t think so. like, it’s been done before, right?? soooo cliched. omg.

Play was very stupid it sucks no one should read it because there is no point of reading this because all this play is taking up your time.

English class will not be fun this year

This is probably the most cliche novel ever written. It’s boring as well and isn’t even in English. Fail!

This absolutely SUCKS!!!!!!!!!!!!!

If you are here looking for a good read for casual use, I would go in search elsewhere. The times have changed and this did not keep my attention. I’m it was a big hit back in its time.

The most boring read ever! The main character spends all his time doing nothing — and, worse, makes us all listen to his tedious CONTEMPLATIONS on how he does nothing. Much too slow; there should be more action here. Moreover, the author reverts time and time again to tired cliches — e.g., “outrageous fortune,” “murder most foul,” “primrose path,” “the time is out of joint,” “more honored in the breach than the observance.” The list could go on and on: we’ve heard them millions of times before, and we hear them every day. Finally, the story is too grim and sad. Why do so many people have to die? Why can’t the main character just realize that it’s better to forgive and forget than to take revenge and CONSTANTLY PONTIFICATE about EVERYTHING. Stay away from this book. There are lots of better and more entertaining books to buy.

It is a little hard to read since its likes a script but I guess it is alright, though it would be better if it is written in story like.

The beginning of every line is a capital letter no matter if it is a new sentence. I don’t know if it ought to be like that, but I don’t like it.

Man, this English was older than my mom. I was like, “What is this?”

If you enjoy confused characters, boring plots, and massive amounts of footnotes, this book about nothing is for you.

Crossing Brooklyn Ferry by Walt Whitman

1

Flood-tide below me! I see you face to face!

Clouds of the west—sun there half an hour high—I see you also face to face.

Crowds of men and women attired in the usual costumes, how curious you are to me!

On the ferry-boats the hundreds and hundreds that cross, returning home, are more curious to me than you suppose,

And you that shall cross from shore to shore years hence are more to me, and more in my meditations, than you might suppose.

2

The impalpable sustenance of me from all things at all hours of the day,

The simple, compact, well-join’d scheme, myself disintegrated, every one disintegrated yet part of the scheme,

The similitudes of the past and those of the future,

The glories strung like beads on my smallest sights and hearings, on the walk in the street and the passage over the river,

The current rushing so swiftly and swimming with me far away,

The others that are to follow me, the ties between me and them,

The certainty of others, the life, love, sight, hearing of others.

Others will enter the gates of the ferry and cross from shore to shore,

Others will watch the run of the flood-tide,

Others will see the shipping of Manhattan north and west, and the heights of Brooklyn to the south and east,

Others will see the islands large and small;

Fifty years hence, others will see them as they cross, the sun half an hour high,

A hundred years hence, or ever so many hundred years hence, others will see them,

Will enjoy the sunset, the pouring-in of the flood-tide, the falling-back to the sea of the ebb-tide.

3

It avails not, time nor place—distance avails not,

I am with you, you men and women of a generation, or ever so many generations hence,

Just as you feel when you look on the river and sky, so I felt,

Just as any of you is one of a living crowd, I was one of a crowd,

Just as you are refresh’d by the gladness of the river and the bright flow, I was refresh’d,

Just as you stand and lean on the rail, yet hurry with the swift current, I stood yet was hurried,

Just as you look on the numberless masts of ships and the thick-stemm’d pipes of steamboats, I look’d.

I too many and many a time cross’d the river of old,

Watched the Twelfth-month sea-gulls, saw them high in the air floating with motionless wings, oscillating their bodies,

Saw how the glistening yellow lit up parts of their bodies and left the rest in strong shadow,

Saw the slow-wheeling circles and the gradual edging toward the south,

Saw the reflection of the summer sky in the water,

Had my eyes dazzled by the shimmering track of beams,

Look’d at the fine centrifugal spokes of light round the shape of my head in the sunlit water,

Look’d on the haze on the hills southward and south-westward,

Look’d on the vapor as it flew in fleeces tinged with violet,

Look’d toward the lower bay to notice the vessels arriving,

Saw their approach, saw aboard those that were near me,

Saw the white sails of schooners and sloops, saw the ships at anchor,

The sailors at work in the rigging or out astride the spars,

The round masts, the swinging motion of the hulls, the slender serpentine pennants,

The large and small steamers in motion, the pilots in their pilot-houses,

The white wake left by the passage, the quick tremulous whirl of the wheels,

The flags of all nations, the falling of them at sunset,

The scallop-edged waves in the twilight, the ladled cups, the frolicsome crests and glistening,

The stretch afar growing dimmer and dimmer, the gray walls of the granite storehouses by the docks,

On the river the shadowy group, the big steam-tug closely flank’d on each side by the barges, the hay-boat, the belated lighter,

On the neighboring shore the fires from the foundry chimneys burning high and glaringly into the night,

Casting their flicker of black contrasted with wild red and yellow light over the tops of houses, and down into the clefts of streets.

4

These and all else were to me the same as they are to you,

I loved well those cities, loved well the stately and rapid river,

The men and women I saw were all near to me,

Others the same—others who look back on me because I look’d forward to them,

(The time will come, though I stop here to-day and to-night.)

5

What is it then between us?

What is the count of the scores or hundreds of years between us?

Whatever it is, it avails not—distance avails not, and place avails not,

I too lived, Brooklyn of ample hills was mine,

I too walk’d the streets of Manhattan island, and bathed in the waters around it,

I too felt the curious abrupt questionings stir within me,

In the day among crowds of people sometimes they came upon me,

In my walks home late at night or as I lay in my bed they came upon me,

I too had been struck from the float forever held in solution,

I too had receiv’d identity by my body,

That I was I knew was of my body, and what I should be I knew I should be of my body.

6

It is not upon you alone the dark patches fall,

The dark threw its patches down upon me also,

The best I had done seem’d to me blank and suspicious,

My great thoughts as I supposed them, were they not in reality meagre?

Nor is it you alone who know what it is to be evil,

I am he who knew what it was to be evil,

I too knitted the old knot of contrariety,

Blabb’d, blush’d, resented, lied, stole, grudg’d,

Had guile, anger, lust, hot wishes I dared not speak,

Was wayward, vain, greedy, shallow, sly, cowardly, malignant,

The wolf, the snake, the hog, not wanting in me,

The cheating look, the frivolous word, the adulterous wish, not wanting,

Refusals, hates, postponements, meanness, laziness, none of these wanting,

Was one with the rest, the days and haps of the rest,

Was call’d by my nighest name by clear loud voices of young men as they saw me approaching or passing,

Felt their arms on my neck as I stood, or the negligent leaning of their flesh against me as I sat,

Saw many I loved in the street or ferry-boat or public assembly, yet never told them a word,

Lived the same life with the rest, the same old laughing, gnawing, sleeping,

Play’d the part that still looks back on the actor or actress,

The same old role, the role that is what we make it, as great as we like,

Or as small as we like, or both great and small.

7

Closer yet I approach you,

What thought you have of me now, I had as much of you—I laid in my stores in advance,

I consider’d long and seriously of you before you were born.

Who was to know what should come home to me?

Who knows but I am enjoying this?

Who knows, for all the distance, but I am as good as looking at you now, for all you cannot see me?

8

Ah, what can ever be more stately and admirable to me than mast-hemm’d Manhattan?

River and sunset and scallop-edg’d waves of flood-tide?

The sea-gulls oscillating their bodies, the hay-boat in the twilight, and the belated lighter?

What gods can exceed these that clasp me by the hand, and with voices I love call me promptly and loudly by my nighest name as I approach?

What is more subtle than this which ties me to the woman or man that looks in my face?

Which fuses me into you now, and pours my meaning into you?

We understand then do we not?

What I promis’d without mentioning it, have you not accepted?

What the study could not teach—what the preaching could not accomplish is accomplish’d, is it not?

9

Flow on, river! flow with the flood-tide, and ebb with the ebb-tide!

Frolic on, crested and scallop-edg’d waves!

Gorgeous clouds of the sunset! drench with your splendor me, or the men and women generations after me!

Cross from shore to shore, countless crowds of passengers!

Stand up, tall masts of Mannahatta! stand up, beautiful hills of Brooklyn!

Throb, baffled and curious brain! throw out questions and answers!

Suspend here and everywhere, eternal float of solution!

Gaze, loving and thirsting eyes, in the house or street or public assembly!

Sound out, voices of young men! loudly and musically call me by my nighest name!

Live, old life! play the part that looks back on the actor or actress!

Play the old role, the role that is great or small according as one makes it!

Consider, you who peruse me, whether I may not in unknown ways be looking upon you;

Be firm, rail over the river, to support those who lean idly, yet haste with the hasting current;

Fly on, sea-birds! fly sideways, or wheel in large circles high in the air;

Receive the summer sky, you water, and faithfully hold it till all downcast eyes have time to take it from you!

Diverge, fine spokes of light, from the shape of my head, or any one’s head, in the sunlit water!

Come on, ships from the lower bay! pass up or down, white-sail’d schooners, sloops, lighters!

Flaunt away, flags of all nations! be duly lower’d at sunset!

Burn high your fires, foundry chimneys! cast black shadows at nightfall! cast red and yellow light over the tops of the houses!

Appearances, now or henceforth, indicate what you are,

You necessary film, continue to envelop the soul,

About my body for me, and your body for you, be hung out divinest aromas,

Thrive, cities—bring your freight, bring your shows, ample and sufficient rivers,

Expand, being than which none else is perhaps more spiritual,

Keep your places, objects than which none else is more lasting.

You have waited, you always wait, you dumb, beautiful ministers,

We receive you with free sense at last, and are insatiate henceforward,

Not you any more shall be able to foil us, or withhold yourselves from us,

We use you, and do not cast you aside—we plant you permanently within us,

We fathom you not—we love you—there is perfection in you also,

You furnish your parts toward eternity,

Great or small, you furnish your parts toward the soul.

I Know What Love Is

Ansel Adams letter to his best friend, Cedric Wright, June 19, 1937.

A strange thing happened to me today. I saw a big thundercloud move down over Half Dome, and it was so big and clear and brilliant that it made me see many things that were drifting around inside of me; things that related to those who are loved and those who are real friends.

For the first time I know what love is; what friends are; and what art should be.

Love is a seeking for a way of life; the way that cannot be followed alone; the resonance of all spiritual and physical things. Children are not only of flesh and blood — children may be ideas, thoughts, emotions. The person of the one who is loved is a form composed of a myriad mirrors reflecting and illuminating the powers and thoughts and the emotions that are within you, and flashing another kind of light from within. No words or deeds may encompass it.

Friendship is another form of love — more passive perhaps, but full of the transmitting and acceptance of things like thunderclouds and grass and the clean granite of reality.

Art is both love and friendship, and understanding; the desire to give. It is not charity, which is the giving of Things, it is more than kindness which is the giving of self. It is both the taking and giving of beauty, the turning out to the light the inner folds of the awareness of the spirit. It is the recreation on another plane of the realities of the world; the tragic and wonderful realities of earth and men, and of all the inter-relations of these.

I wish the thundercloud had moved up over Tahoe and let loose on you; I could wish you nothing finer.

Source: http://www.lettersofnote.com/2012/01/i-know-what-love-is.html

Examples of Discursive Materialization of The Body

Consider this sense of biology from The Problemes of Aristotle,

a well-used Elizabethan medical guide that emphasizes male procreativity,

sub-ordinating the role of the female:

The seede [of the male] is the efficient beginning of the childe, as the builder is the efficient cause of the house, and therefore is not the materiall cause of the childe….The seedes [ie both male and female] are shut and kept in the wombe: but the seede of the man doth dispose and prepare the seede of the woman to receive the forme, perfection, or soule, the which being done, it is converted into humiditie, and is fumed and breathed out by the pores of the matrix, which is manifest, bicause onely the flowers [ie the menses] of the woman are the material cuase of the young one.

_____

Nay, but this dotage of our general’s

O’erflows the measure: those his goodly eyes,

That o’er the files and musters of the war

Have glow’d like plated Mars, now bend, now turn,

The office and devotion of their view

Upon a tawny front: his captain’s heart,

Which in the scuffles of great fights hath burst

The buckles on his breast, reneges all temper,

And is become the bellows and the fan

To cool a gipsy’s lust….

Shakespeare, Antony and Cleopatra. I.i.1-10_____

When summer swims off, mild and pale, they have already sucked up love like sponges, and they’ve turned back into animals, childish and wicked, with fat bellies and dripping breasts, completely shapeless, and with wet, clinging arms like slimy squids. And their bodies disintegrate, and are sick unto death. And with a ghastly outcry, as if a new world were on the way, they give birth to a small piece of fruit. They spit out in torment what once they had sucked up in lust

Bertolt Brecht, Baal._____

Do you have a prayer book in your kerchief?

Do you have golden tresses down to your shoulders?

Do you lower your eyes quickly down to your apron?

Do you hold onto your mother’s skirts?

. . .

It is no good; were my arms as long

As pine branches or spruce limbs–

I know I could not hold her far enough away

To set her down from me unsoiled and pure.

Henrik Ibsen, Peer Gynt._____

I wanted to create that pure woman in the form in which I saw her awakening on Resurrection Day. Not astonished at anything new or unfamiliar or unimagined, but filled with a sacred joy as she discovers herself again–unchanged–she, the woman of the earth–in the higher, freer, happier regions–after the long dreamless sleep of death.

Henrik Ibsen, When We Dead Awaken._____

her body was all wrong, the peacock’s claws. Yes, even at that early stage, definitely all wrong. Poppata, big breech, Botticelli thighs, knock-knees, ankles all fat nodules, wobbly, mammose, slobbery-blubbery, bubbubbubbub, a real button-bursting Weib, ripe. Then, perched aloft this porpoise prism, the loveliest little pale firm cameo of a birdface he ever clapped his blazing blue eyes on. By God he often thought she was the living spit of Madonna Lucrezia del Fede.

Samuel Beckett, Dream of Fair to Middling Women.

Human / Non Human

When you incorporate human figures/actors in a performance

with non-human technologies

i.e., film, video, recorded sound, holograms,

do the human figures signify

sustain reference as signs

in a differentl way

than the technological?

What happens to each of the elements

(human/non human)

in the interaction or co-presence,

if they are not interactive?